Question #fb8a1

1 Answer

You can do it like this:

Explanation:

Your question does not use Slater's Rules. Since you want to understand these in your sub - note I will use these rules in my answer.

Consider an atom like sodium in the gaseous state:

Sodium has 11 protons in its nucleus i.e

The presence of the other 10 electrons in red has the effect of "shielding" or "screening" the outer electron from the attractive force of the nucleus.

This means that it experiences an attraction for the nucleus which is less than you would expect from the 11 protons.

This is referred to as the "effective nuclear charge" or

So we can write:

Where

In 1930 John Slater worked out a method of calculating this screening effect which are known as "Slater's Rules".

Electrons are grouped together in increasing order of

Each group has its own shielding constant. This depends on the sum of these contributions:

1.

The number of electrons in the same group.

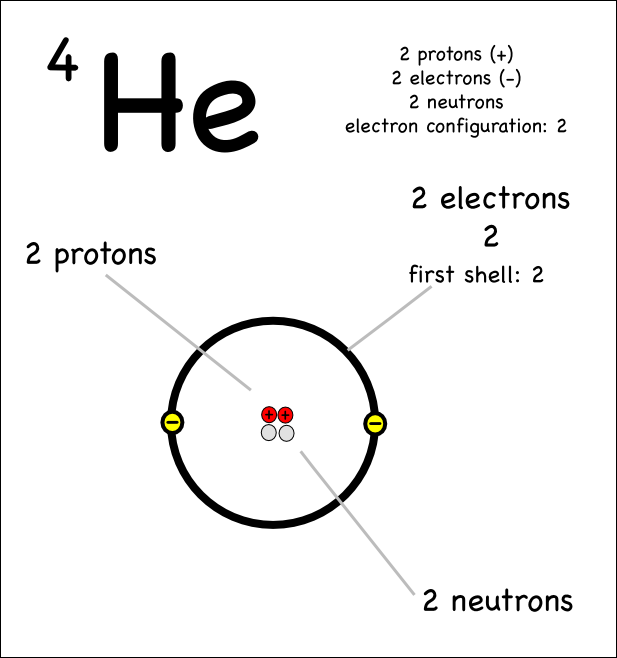

You might think that the 2 electrons in helium are not able to shield each other since they are the same distance from the nucleus using the Bohr model:

However if you look at the probability of finding an

Point C is referred to as "The Bohr Radius" but you can see that there is some probability of the electron being at points closer to the nucleus such as A and B.

This means that the

2.

The number and type of electrons in the preceding groups.

The total shielding constant is, therefore, the overall shielding effect from

For

0.35 for each other electron within the same group, except for

For

For

Lets see how this applies to the examples in your comment:

So

Within the [2s and 2p] group a single 2p electron will be shielded by 7 other electrons each contributing 0.35 and below the group there are 2 x 1s electrons each contributing 0.85.

But this time

So

This shows that a 2p electron in